Actualités

Peasants caught in the industrial property backwater

Privatizing seeds, the first link in the food chain, seems to be the obsession of the seed industry, which would thus control all the world’s food. One of the battles on farmers’ rights to their seeds will take place during the eighth meeting of the Governing Body of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, in Rome, from 11 to 16 November 2019. The defence of peasant seed systems, which form the basis of the food supply for the majority of rural people, will be a central issue.

In 2019, four agrochemical multinationals hold more than 60% of the world’s commercial seed market [1], compared to eight just seven years ago [2]. Bayer acquired Monsanto; Dow and Dupont merged and created Corteva, their agricultural subsidiary; ChemChina acquired Syngenta; and BASF acquired parts of Bayer. The concentration of the seed industry is accelerating, based on a parallel extension of industrial property claims, allowing these companies to prohibit farmers from resowing “protected” varieties.

Over the last fifty years, industrial patent law has spread like a gangrene over all life forms. The lawyer Marie-Angèle Hermitte points out that « since 1963, the proponents of patents have gained several forts that now constitute new tactical positions: patents granted directly on microorganisms, and no longer on the processes for obtaining them; patentability of cells, assimilated to microorganisms, and the genes found therein, including human cells and genes…. » [3].

This extension of the patent system, which seems to have no limits, directly affects cultivated plants. In particular, peasant seed systems that abound with genetic resources can now be appropriated. Legal frameworks are strengthened around a vision established in the European Directive 98/44 on the legal protection of biotechnological inventions that reduces life to “biological material”. This subsequently allows the European Patent Office to unilaterally decide that a “plant defined by recombinant DNA sequences (…) is no longer a living being (…). An abstract definition is open encompassing an indefinite number of individual entities defined by a part of their genotype or by a part that it has conferred on them” [4]. And the ambitious project to digitize all the world’s genetic resources raises concerns that they will all eventually be privatized [5]. M.-A. Hermitte reminds legislators that “the most absolute rights, such as the right to property, must assume a horizon of what is called the social function of the right to property”. That remains unanswered today.

Seed laws: a battle waged by industry against farmers

Farming systems that are self-sufficient in seeds are still largely in the majority: they feed more than 70% of the population [6]. These peasant seeds are sometimes also identified as traditional, local, old. The Réseau semences paysannes (RSP), which brings together about a hundred organizations supporting organic and peasant agriculture in France, defines them as follows: “seeds selected and reproduced by farmers in their production fields. (…) Their characteristics make them adaptable to the diversity and variability of soils, climates, farming practices and human needs without the need for chemical inputs. Reproducible and not appropriable by title, these seeds are exchanged in accordance with user rights defined by the collectives that selected and saved them” [7]. Commercial seeds, those registered in catalogues and most often subject to industrial property rights, represent only 25% of all seeds used in the world by farmers [8]. However, farmers are under constant pressure to abandon their seeds. They regularly meet in different parts of the world to defend their increasingly threatened rights. Thus, the next International Meetings of Farmers’ Seeds, in Occitania (Mèze, November 7 to 9, 2019), will bring together several hundred farmers from around the world around the rallying cry “Sow your resistance” [9].

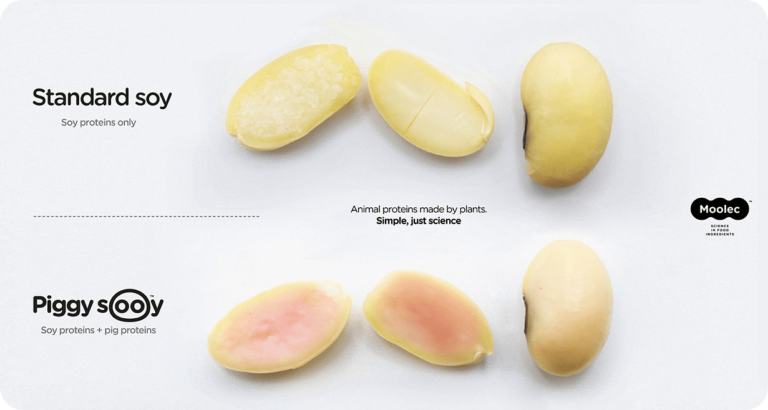

The seed industry is working to reverse this ratio: what could be more lucrative than forcing a farmer to go to a seed seller at the beginning of each agricultural cycle? To do this, two types of instruments are used. The first is the biological patent that breeders introduce into plants: seed harvested at the end of an agricultural cycle does not regrow, or the variety is denatured. In this case, the farmer must buy fresh seed to avoid a poor harvest the following year. Seeds used in vegetable farming and production of some major crops such as corn are F1 hybrids [10].

The second category of measures involves the implementation of legal obstacles. By getting a property right on seed, a seed company prohibits farmers from resowing the plants harvested from their crop (in the case of patents), or obliges them to pay the company royalties on the use of the variety (in the case of plant variety protection certificates as set up by the Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants – UPOV). In another legal area, the legislation prohibits the marketing of seeds of peasant varieties. Indeed, these varieties are too heterogeneous, according to the technical criteria required by the industry, to be included in registers or catalogues, set up as a prerequisite for being allowed to be on the market.

International seed treaty: farmers’ rights difficult to acquire and little applied

The modern variety was not created ex nihilo: it is the result of varieties previously collected from the fields of these farmers. Bred or genetically modified by the seed company, it is protected by a property right that obliges farmers to pay for access to it. Since the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, however, the terms of trade have been disrupted. The Convention, ratified by 196 countries – with the notable exception of the United States – recognizes the sovereignty of each State over its biological resources. From then on, access permits are required in order to collect a biological resource and the sharing of the benefits arising from the exploitation of these resources is mandatory.

This caused a drama within the seed industry which until then had freely used peasant seeds in the name of the “Common Heritage of Humanity”. Would it now be necessary to ask for authorization for each variety a breeder would cross, fore each genetic resource used? Since 1983, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) promoted an “International Undertaking on plant genetic resources” [11], on the one hand to help countries in the South preserve them, but above all to allow their free international flow whether for conservation or breeding. The Undertaking was shaky with the new sovereignty of States over their resources. It was therefore necessary to find a new agreement to facilitate the work of seed companies, which was reflected in the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture and Food (ITPGRFA) in 2001.

The name is abstruse to the uninitiated, and poorly reflects the crucial societal issues it envelopes. Indeed, ITPGRFA is the international treaty on cultivated plants, and the only one to explicitly include farmers’ rights on their seeds. It recognizes “the immense contribution of farmers to the development of the wealth of plant genetic resources”. Very concretely, more than half of the seven million seed samples stored as genetic resources in the world’s gene banks come from farmers’ seed systems on all continents [12].

Through the ITPGRFA, seed companies have secured, for 64 cultivated species, “facilitated access to plant genetic materials for collectors (private or public, amateur or professional), plant breeders (seed companies, farmers…), scientists and educational institutions” [13]. ITPGRFA also recognizes the “right of farmers to participate equitably in the sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, [as well as] the right to participate in national decision-making on matters relating to the conservation and sustainable use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture” [14]. However, these fundamental rights are “subject to national law” (Article 9.3 of the Treaty). This requires the construction of spaces for consultation in each country between farmers’ organizations and the State, under the pressure of the economic interests of an increasingly powerful seed industry.

Since the entry into force of ITPGRFA in 2004, meetings of the Treaty’s governing body have been held every two years to discuss its implementation. There is a systematic battle between the interests of seed companies – indirectly represented by some OECD countries – and farmers’ rights, with several countries of the South (such as Ecuador and Bolivia) acting as spokespersons. The industrialised countries are calling for an extension of the Treaty to all cultivated species. Farmers, on the other hand, simply wish to realize their rights to “save, use, exchange and sell farm-saved seeds or propagating material”.

The Expert Group’s loaded game

The president of the Convergence of Rural Women for Food Sovereignty (COFERSA), Alimata Traoré, represents several thousand women farmers organized in a network of rural women’s cooperatives in Mali. Its organization is very active in the promotion of biodiversity cultivated for food, within the West African Peasants’ Seed Coordination (COASP). This network multiplies the spaces for the exchange of seeds and know-how throughout the sub-region (training in breeding, peasant seed houses, seed exchange fairs, workshops). COFERSA, together with all the organizations of the National Coordination of Peasant Organizations of Mali (CNOP), are campaigning for the recognition of peasant seed systems and farmers’ rights. This work has recently led to the establishment of a consultation framework officially led by the Ministry of Agriculture. Alimata Traoré was appointed by the farmers’ organizations to represent them in the negotiations of the Ad Hoc Expert Group on Farmers’ Rights set up by the Treaty Secretariat. She sits there with two other farmers facing a learned assembly of about fifty experienced technicians, including several industry experts. The working language is English. As the only French-speaking peasant, she is supported by the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC) to make its voice heard. This autonomous and self-organized global platform of small-scale food producers, rural workers’ organizations and social and community movements (800 organizations representing 300 million people) aims to advance the implementation of food sovereignty at the global and regional levels. IPC denounces the obstructions to negotiation: « After two meetings where industry and a handful of rich countries systematically obstructed, this group of experts succeeded in producing only a application form for identifying essentially technical experiences of national applications of farmers’ rights. While rights are first and foremost expressed in laws, it is very difficult to integrate into this form the political and legal conditions for the success of each of these technical experiments and, to date, there is no guarantee that the work of this group of experts will continue or that it will function better“ [15].

Alimata Traoré testifies: “Farmers in West Africa and around the world are constantly maintaining and developing biodiversity through their seed systems. What they need is legal recognition and protection of these peasant seed systems and our traditional knowledge. Without adequate laws, farmers’ rights are not effective. However, we note that some members of the expert group do not want to move forward and are pushing for the extension of breeders’ intellectual property rights” [16]

The regulatory straitjacket imposed by industrial countries on Africa

Farmers’ seed systems ensure the continued availability of the vast majority of seeds and seedlings of plant varieties grown in African countries. They are fundamental to enable rural communities to ensure their food sovereignty. As in all countries in the region, international donors are gradually imposing a regulatory straitjacket on seeds. It is carried out in four areas: three of them – seed marketing, GMO release, and industrial property rights on plants – are built on their backs and at their expense. Only the register of the conservation and sustainable use of genetic resources defined by the Treaty opens a door for the recognition of their rights. In theory, these rights are supposed to allow farmers who maintain biodiversity in their fields to fully enjoy autonomy in the management of their seed activity. But these rights are not yet implemented because it is up to States to guarantee legislative and regulatory measures, with governments under the strong influence of the proponents of the global liberal economy.

In the field of seed marketing, Mali is one of the 15 States subject to ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) seed regulations, where efforts to harmonize seed legislation are under way. The African Center for Biodiversity (ACB), a South African NGO promoting agro-ecology and farmers’ seed systems, notes that the harmonization of seed legislation initiatives in Africa’s four economic regions is based on common imperatives: reducing transaction costs for the seed industry through similar regulatory and trade provisions between and within regions. The scenario envisaged is the free movement of certified seed.

The harmonization of seed regulations is seen as an essential driver of the transformation of agriculture towards industrialized agricultural systems and expanded industrial seed markets. It expressly supports specialisation, i.e. the integration of farmers into the system either as seed producers who must comply with the requirements of the ECOWAS Regulation and focus solely on seed production or as seed users. In this vision, most farmers must buy seeds and leave seed production to specialists.

The harmonisation of regulations favourable to the seed industry also concerns the distribution facilities for GMO plants. The ECOWAS regulation on the free movement of GMOs has just been adopted [17] without farmers’ organisations being able to express their views. Nigeria already allows the release of GM crops for human consumption (cowpea, cassava, rice…) [18], and pressure from seed industries is very high. In 2012, Burkina Faso adopted biosafety regulations that allowed it to grow GMO cotton, a crop abandoned following major commercial setbacks [19]. Senegal [20], Benin, Niger, Nigeria, Ghana are also implementing such biosafety laws, implementing harmonized biosafety regulations at the regional level.

In the field of industrial property, Mali is a member of the African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI), a signatory to the Bangui Agreement, strongly inspired by the French model and rooted in a liberal economics. It is a single law that serves as national legislation for all Member States. Today, OAPI has 17 Member States: all the French-speaking countries of West and Central Africa, Guinea Bissau, Equatorial Guinea and the Comoros. The headquarters of the organization is in Yaoundé (Cameroon).

The Bangui Agreement was revised in 1999, in particular to respond to the compliance of the newly established agreement on trade-related intellectual property rights of the World Trade Organization (WTO). As soon as the Bangui Agreement entered into force on January 1, 2006, plant variety protection (PVP) certificates on new variety became available in all OAPI Member States. And the criteria of novelty, distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS), which are the standards for UPOV, have been adopted for plant variety protection.

A certificate of plant variety protection is a powerful industrial property instrument in accordance with the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention. It confers on its owner the exclusive right to exploit the variety: to produce and reproduce it, to package it for reproduction, to offer it for sale, marketing, export and import. This also applies to the product of the harvest obtained as a result of unauthorized use of the propagating material of the protected variety. In the OAPI system, the exception of the “farmer’s privilege” to use the variety on his or her own farm is an optional exception leaving countries the discretion to grant it or not. The privilege is considerably reduced in Bangui Agreement since it does not apply to fruit, forest and ornamental varieties, which are the main export crops.

A study on the effectiveness of the plant variety protection system in the OAPI space after ten years of operation [21] reveals the failure of this system. The study highlights the difficulties of obtaining information, due to the lack of dedicated structures, updated information on the website, a liaison bulletin, etc. Nevertheless, the lawyer Mohamed Coulibaly and his co-authors have been able to show that in ten years OAPI has received 122 applications for variety protection from six member countries (only one third of the signatory countries), of which only 51 are in force: the majority of titles belonging to public research have lapsed for non-payment of annual fees. This is not surprising: encouraged by donors, the public agricultural research sector in African countries was 80% involved in the first PVP applications. However, it is this sector that traditionally produces the vast majority of varieties for farmers, without seeking to promote them commercially, since this work corresponds to their role as a public entity. Since the protection of a variety by PVP amounts to several thousand euros (application fee, publication fee, annual rent over 25 years, etc.), which is not available to public research, the institution quickly finds itself forced to protect. “The bird is in the cage,” says a Malian research manager bitterly. The only interest to pay in full would be to obtain “defensive protection” against potential biopiracy [22].

Indeed, in the OAPI/UPOV system, public researchers, just like farmers and local communities who have managed traditional varieties, run the risk of one day being deprived of them and even of no longer being able to use them freely because of the protection rights granted to breeders on their barely stabilized varieties (see box).

Hold up of peasant varieties: instructions for use

The Violet de Galmi onion from Niger is a well-known peasant variety. In 2006, the seed company Tropicasem SA, a subsidiary of Technisem France in Senegal, claimed ownership of this variety. This claim was contested by the Government of Niger, alerted by its technical services, which were themselves referred to by the Niger farmers’ platform, which had obtained the information at the Djimini Regional Farmers’ Seed Fair in Senegal [23]. OAPI accepted to Niger’s request and refused to allocate the PVP title to Tropicasem under the name Violet de Galmi. The seed company then renamed the variety Violet de Damani to renew its application to the OAPI, which finally granted it the PVP certificate in 2015 (certificate #106 issued on 27/02/2015). But the characteristics of the variety are the same as those of Violet de Galmi onion, so Niger has filed a new opposition that has remained unresolved [24].

The opposition between the government of Niger and Tropicasem raised the fundamental question of the protection of a peasant variety following a selection process that led to the homogenization and stabilization of the variety. OAPI has only examined the part of the problem related to variety denomination. It establishes that peasant varieties cannot be protected because they do not meet DUS criteria. It also confirms that a breeder has the right to purify and stabilize a traditional variety without changing its key characteristics and obtain PVP on it. This indicates a potential conflict between UPOV-type treaties and the Convention on Biological Diversity, which requires the agreement of suppliers of genetic resources, in this case Niger, and benefit-sharing between the breeder and these suppliers, including local communities that have conserved the resource in question. The same is true of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture hosted by FAO [25].

After ten years of operation under the Bangui agreement, the situation is simple: no dedicated structures, no massive creation of new varieties, no emergence of a private seed sector, but the installation of a great unease among peasant organizations, researchers and unconvinced national legislators. The grafting of the UPOV system, already criticized in the North, “thought with the agricultural systems of developed countries in mind” [26] has absolutely not taken hold, but despite its obvious failures, OAPI persists: on September 23, in Lomé (Togo), it launched a project to strengthen and promote the plant variety protection system [27].

Intellectual property rights expanding over life forms

For seed companies, the future lies in patents. The European Directive 98/44 on the legal protection of biotechnological inventions has given a considerable extension to patents on DNA sequences. It adopts as a general principle that the protection conferred by the patent on a biological material or genetic information extends to everything that includes that material and that information. Also, claims of appropriation by patent are multiplying. Thanks to new “big data” algorithms, it is becoming easy to establish links between genetic information data and new plant traits and the products identified by these techniques. All of them are patentable. Therefore, stresses Guy Kastler, La Via Campesina farmer, “if patents and market access are still granted without the obligation to provide information on the origin of genetic resources and digital sequencing information used to develop patented and marketed products, no fair benefit sharing can be achieved. (…) This open access to digital sequencing information announces the death of prior informed consent and benefit-sharing put in place by the CBD (…) or by the Multilateral Facilitated Access System of the ITPGRFA.” [28]. On this matter, La Via Campesina asks, “Should we accept the planned disappearance of the International Seed Treaty?” [29]

Peasants’ rights: the United Nations Declaration

The emergence of a new, more ethical system, at a time when the stronghold of industrial property is spreading like cancer to the living world, remains a challenge. However, in December 2018, a new UN text strengthened the meagre international legislative arsenal to defend the rights of peasants: the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Others Working in Rural Areas.1 This declaration is the result of more than 20 years of hard work by farmers, including La Via Campesina, with the support of NGOs such as FIAN and CETIM. It benefited from the contributions of the Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Food of the Human Rights Council at the United Nations, first Jean Ziegler and then Olivier de Schutter, and from the unfailing support of Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, who was then chairing the intergovernmental working group [30].

In this declaration, article 19 details all the commitments of States in the various international texts, including ITPGRFA, on farmers’ rights to seeds. It stipulates, inter alia, that “peasants and other persons working in rural areas are entitled to the right to seeds, in accordance with Article 28 of this Declaration, which includes: (…) (d) The right to save, use, exchange and sell farm-saved seeds or propagating material.” It also addresses the States: « 6. States shall take appropriate measures to support peasant seed systems and promote the use of peasant seeds and agro-biodiversity. (…) 8. States shall ensure that seed policies, plant variety protection laws and other intellectual property laws, certification schemes and seed marketing laws respect and take into account the rights, needs and realities of farmers and other persons working in rural areas” [31].

Meeting in Dakar in July 2019, the African civil society group preparing the November meeting of ITPGRFA Governing Body encouraged the Treaty bodies to interpret the concepts of farmers’ rights in an approach consistent with this Declaration on the Rights of Peasants, following a clear observation: “Peasants (…) provide almost all of the seed samples from national and international gene banks. They represent more than half of Africa’s population, or at least half a billion human beings. As the most rural continent, where half of the population is agricultural, young and female, the recognition of the rights of peasant women and efforts to include young people in programmes are the conditions for the successful implementation of the Treaty,” it said in particular.

Let’s meet in Rome in mid-November to find out if they will be heard.

[1] Global Seed Industry Changes Since 2013, Philip H. Howard, 2018, https://philhoward.net/2018/12/31/global-seed-industry-changes-since-2013/

[2] Who will control the green economy?, Dec. 2011, ETC Group, p.22, http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/publication/pdf_file/ETC_wwctge_4web_Dec2011.pdf

[3] L’emprise des droits intellectuels sur le monde vivant, Editions Quae, Marie-Angèle Hermitte, 2016

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Sequencing the genome of all living beings on Earth”, Frédéric Prat, August 2019,

[6] Who will feed us, The Industrial Food Chain vs. The Peasant Food Web, 2017, 3rd edition, ETC Group, http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/files/etc-whowillfeedus-english-webshare.pdf

[7] See Ten Measures for Farmers’ Seeds, RSP, 2013 https://www.semencespaysannes.org/images/documents/10_mesures_pour_que_vivent_les_semences_paysannes.pdf

[8] Who will feed us?, Op. Cit.

[10] See La planète des clones, Jean-Pierre Berlan, Ed. La lenteur, June 2019

[11] Resolution 8/83, International undertaking on plant genetic resources, nov. 1983, http://www.fao.org/wiews-archive/docs/Resolution_8_83.pdf

[12] FAO, 2010, The Second Report on the State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Agriculture and Food.

[14] Ibid.

[15] IPC Communiqué

[16] Ibid.

[18] Jean Gecit, “In Nigeria, a new cowpea variety that will bring in big profits”, Commodafrica, 14 June 2019, http://www.commodafrica.com/14-06-2019-au-nigeria-une-nouvelle-variete-de-niebe-qui-va-rapporter-gros

[19] Rémi Carayol, “Bataille autour des semences transgéniques en Afrique”, Le Monde diplomatique, September 2017.

[20] Senegal validates its first National Biosafety Strategy, July 16, 2018, http://www.environnement.gouv.sn/lesactualites/atelier-de-validation-de-la-strat%C3%A9gie-nationale-de-bios%C3%A9curit%C3%A9

[21] Mohamed Coulibaly et al, A Dysfunctional Plant Variety Protection System: 10 years of UPOV implementation in Francophone Africa, Working Paper, APBREBES, BEDE, 2019

[22] See “Porte ouverte au biopiratage”, Guy Kastler, Le Monde diplomatique, April 2006

[23] ASPSP, BEDE, 2009. Journal of the West African Peasant Seed Fair, http://www.bede-asso.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/journalfoire2009.pdf

[24] Author’s interview with Ousmane Abdou, OAPI focal point at the Ministry of Agriculture of Niger, Nov 30, 2016.

[25] See Sangeeta Shashikant, UPOV: Symposium Reveals Conflict in Interrelations Between UPOV and ITPGRFA; UPOV To Consider Proposals. Available here: http://www.apbrebes.org/news/upov-symposium-reveals-conflict-interrelations-between-upov-and-itpgrfa-upov-consider-proposals

[26] Carlos M. Correa et al., Plant Variety Protection for Developing Countries: A Tool for Developing a Sui Generis Plant Variety Protection System as an Alternative to the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention, APBREBES, 2015. p.29.

[27] http://www.commodafrica.com/24-09-2019-loapi-veut-renforcer-le-systeme-de-protection-dobtentions-vegetales

[28] Extract CIP Agenda item 4 – “Information on the numerical sequence”, 2019

[29] See press release, https://www.eurovia.org/should-we-accept-the-planned-disappearance-of-the-international-seed-treaty/

[30] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Farmers and Others Working in Rural Areas, https://undocs.org/fr/A/C.3/73/L.30

[31] On the genesis and birth of this Declaration, see p. 56 et seq. of “The UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants, A Tool for Struggling for a Common Future”, Coline Hubert, CETIM N°42, Geneva, 2019.